3D Topography Sandbox Part of Ocean Discovery Day

Sandboxes are commonly known as a beloved toy of many young children. But sandboxes have uses outside of being a toy—the term “sandbox” has entered the colloquium to refer to thinktanks and computer programs that give users great freedom of use.

In the High Bay of the Jere A. Chase Ocean Engineering Laboratory, home to the Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping and the Joint Hydrographic Center and located behind the Field House, the term refers instead to a literal sandbox – the 3-D topography sandbox, to be specific.

The 3-D topography sandbox is a small part of the High Bay, which takes up much of the building’s first floor, and houses two large water tanks and a variety of equipment often used in teaching and outreach programs. Many booths sat and demonstrations took place in the High Bay during Ocean Discovery Day in October, and the 3-D topography sandbox was a favorite among the 2,400 people that came during the two days of the festivities.

The sandbox is physically a standard one, just raised to stand about three feet high. Technically, though, it is anything but standard—it’s digital; or the program that relies on it is.

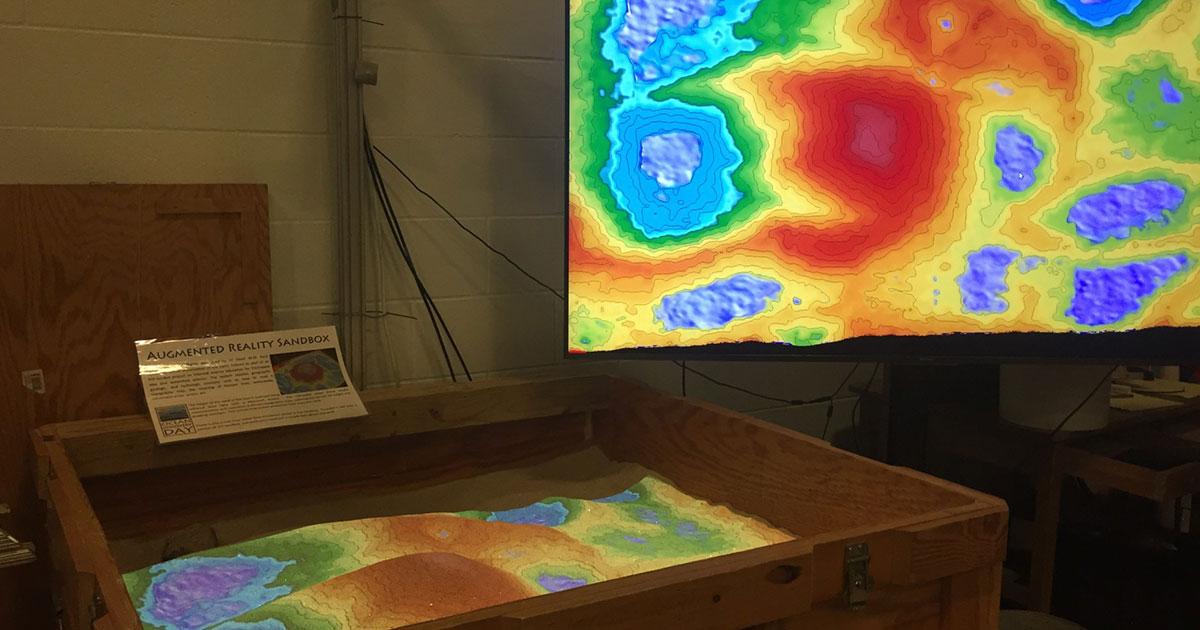

Mounted about five feet above the sandbox is an Xbox Kinect projector, which when turned on projects a series of colors and lines on the sand. These colors change in response to how the sand is scattered across the sandbox—sand piled into a mountain becomes red, while sand scooped away to create a valley turns blue and when deep enough, the blue becomes color of crystalline water, with an undulating wave pattern.

The colors are depicting the sand’s topography, or the rise and altitude of variations in the sand. Topography is used in creating topographic maps, such as of the White Mountains—the squiggly lines drawn around Mount Major delineate how tall it is and how steep or gently sloping its sides are.

When someone pushes the sand or even waves their hand underneath the projector as they move the sand around, the colors and lines change—make the mountain steeper, the lines grow closer together. Wave your fingers up and down, and you might get “drips” of water.

“The Kinect is mapping the surface of the sand, calculating the topography of it… creating a topographic map from that data and then projecting the results back onto itself through the projector,” CCOM Outreach Specialist Tara Hicks Johnson, who oversees outreach to all ages and professions across the country, said. Once the Kinect maps the sand, it also displays it on a 5-foot monitor standing next to the sandbox, showing the 2-D version of the sand’s topography, or what it would like it standard map form.

The program that creates these colors and lines for the sandbox, also called the Augmented Reality Sandbox, originated on the West Coast, explained Hicks Johnson. Funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF) helped the University of California, Davis, and the museums Lawrence Hall of Science and ECHO Lake Aquarium and Science Center, according to UC Davis’s website, build the program.

On the website for the augmented reality sandbox, users can find a section called “Build Your Own,” providing access and instructions for the required software, all free.

“Because the program was developed through the National Science Foundation, that means that the resulting program is free for anybody to download,” Hicks Johnson said.

CCOM, which has research projects spanning everything from applying new techniques to assess gas leaks after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, to understanding the sediment of the seafloor (mapping), decided to “Build [Their] Own” sandbox “because the sandbox relates to a lot of the research that we do here,” Hicks Johnson said. At first, there wasn’t a plan to make the sandbox the permanent installation in the High Bay as it currently is.

“It was a fun test to see how the program worked and we’ve been using it ever since, because people love it,” Hicks Johnson said.

Those people include all ages and all professions. “…If it’s an admiral from NOAA [the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association], if it’s businesspeople…everybody loves the sandbox.”

One demographic that uses the sandbox often is schoolchildren, who will visit the Chase Ocean Engineering Building when covering curriculum units related to marine science. The first day of Ocean Discovery Day was reserved for local schools, so they could bring their students and see the ocean research based at the University of New Hampshire (UNH).

All this usage of the sandbox shows that it is here to stay. “It works perfectly for our facility because we do mapping. We use different tools, we use sonar, which is sound, to map the seafloor, we also use LiDAR, which is kind of like light, lasers, to map the topography also, we’re getting into drones now…the idea of using a tool to map a surface is something that we do a lot here, so it’s a great introduction. We’ll bring kids here first and then bring them into the rest of the building where they can see these 2-dimensional maps on the wall, and it gives them a little bit of a better idea about what they’re looking at,” Hicks Johnson said.

Undergraduate students use the sandbox too, she said. Professors from departments as varied as computer science, kinesiology, civil engineering and ocean engineering have taken classes to the sandbox, using the sandbox as a tool for learning topics such as reading topography and understanding factors involved in building bridges.

“The idea behind it all relates to our visualization lab…We collect so much data that we need to have ways like this so that we can show the data off in ways that people can understand, and can get information, and can find useful,” she said. The Data Visualization Research Lab focuses on novel methods of presenting numbers in visual formats with computer graphics, such showing how water flows. Examples of the lab’s work can be found in the first-floor hallways of the Chase Ocean Engineering Building near the lab.

The sandbox has even inspired other schools to get their own 3-D topography/augmented reality sandbox.

“It’s a zen place…We leave the program running all the time, we just turn off the projector bulb, so that anybody can really, if they [want to] come in and show somebody or if they [want to] play with it themselves, they can just come in themselves and turn the projector on,” Hicks Johnson said. The projector is kept off to keep the bulbs from burning out, and sandbox users should turn the projector off after use, but the sandbox is open to all—or contact Hicks Johnson at Tara.Hicks-Johnson@unh.edu.

“It’s next generation of sandbox play,” she said.

To find an Augmented Reality Sandbox near you, click here.

By Jenna O’del University of New Hampshire